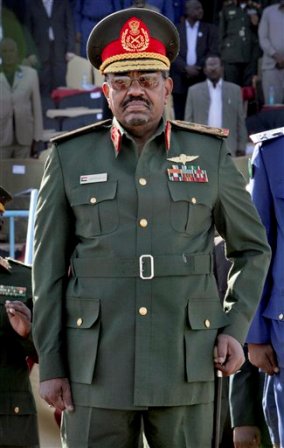

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir attends a graduation ceremony at an air force academy near Khartoum, Sudan, Wednesday, March 4, 2009. Sudan denounced an international tribunal that issued an arrest warrant against its president Wednesday on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, calling it a "white man's court" that aims to destabilize the country. (AP Photo/Abd Raouf)

By Anthony Dworkin and Katherine Iliopoulos

The International Criminal Court announced on March 4, 2009 that it was issuing an arrest warrant against Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir for masterminding a campaign of crimes against humanity and war crimes by government troops and Arab militias in the Darfur region. The announcement, coming eight months after the Court’s prosecutor requested an arrest warrant, marks the first time that the ICC has sought the arrest of a sitting head of state. The Court decided not to proceed with the charges of genocide, ruling that there did not exist reasonable grounds upon which a finding could be made that al-Bashir had the necessary genocidal intent.

Following the announcement, al-Bashir suspended the operation of 13 aid organizations in Sudan, saying they had cooperated with the ICC by supplying information. He later said that he wanted all foreign aid organizations to leave within a year. The ICC’s announcement and the Sudanese response have generated much debate, but there has been comparatively little discussion about how al-Bashir might be delivered to the Court.

The Arrest Warrant and the Personal Immunity of Incumbent Heads of State

Announcing its decision to issue an arrest warrant, the Court’s Pre-Trial Chamber I asked the Court’s registrar to prepare a request for cooperation for President al-Bashir’s arrest and transmit it to Sudan, to all States Parties to the Rome Statute, to all United Nations Security Council members that are not party to the Statute, and to any other State as may be necessary. The Registrar duly prepared communications to Sudan, the States Parties, and to those members of the Security Council not party to the Statute. Presumably it is keeping open the option of sending a communication to any other state if the need arises.

Welcoming the announcement, the Court’s Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo said that Sudan was obliged under international law to execute the warrant of arrest on its territory, and that “as soon as Omar al-Bashir travels through international air space, he can be arrested.”

However the question of al-Bashir’s arrest may be more complicated than the Court’s requests and the prosecutor’s statement suggest, because of his position as Sudan’s head of state.

Under international law, the doctrine of sovereign or diplomatic immunity means that certain holders of high-ranking office in a State such as the Head of State enjoy immunities from jurisdiction in other States, both civil and criminal. That means that national courts are unable to try a high official of another state who is suspected of committing crimes - no matter how serious - as this would constitute a violation of state sovereignty. The United Nations is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all member states, whereby a state is not permitted to interfere in affairs that are within the domestic jurisdiction of another state. Sovereign immunity covers both a head of state and the state itself. Personal immunity only extends to incumbent heads of state; in the case of DRC v Belgium, the International Court of Justice said this was necessary in order for the head of state to be able to exercise his functions effectively.

There is little question that al-Bashir could be prosecuted before the ICC. According to Pre-Trial Chamber I, “al-Bashir’s official capacity as a sitting Head of State does not exclude his criminal responsibility, nor does it grant him immunity against prosecution before the ICC.” There are many precedents for international courts issuing indictments against sitting heads of state, and Article 27 of the Rome Statute of the ICC explicitly provides that the Statute applies equally to all persons without distinction based on their official capacity.

However the ICC does not have its own police force, and the Security Council has not authorized any international force to arrest him. He is only likely to face justice if he is arrested and transferred to the Court by the authorities of a State. Could a State do so without violating its legal obligation to respect his immunity as head of state?

Arrest and Surrender by Sudan

Sudan signed the Rome Statute in 2000 but has not yet ratified it. However the UN Security Council, in Resolution 1593 (2005) referred the situation in Darfur to the ICC Prosecutor, thereby granting the ICC jurisdiction over the matter.

In granting jurisdiction, the Security Council could be assumed to have also applied the provision in the Rome Statute that overrides any claim of immunity for heads of state. (This was the view taken by the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber, which said that the Security Council had accepted that investigations and prosecutions from Darfur “will take place in accordance with the statutory framework provided for in the Statute, the Elements of Crimes and the Rules as a whole.”) Even if the Security Council did not by implication apply this provision, there is arguably no immunity of heads of state from prosecution before international tribunals under customary international law.

The Resolution was passed under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, which gives the force of international law to Security Council resolutions concerning the maintenance of international peace and security. Paragraph 2 of Resolution 1593 says that the Security Council “Decides that the Government of Sudan and all other parties to the conflict in Darfur shall cooperate fully with and provide any necessary assistance to the Court and the Prosecutor.” Therefore Sudan has an obligation under international law to surrender anyone sought by the ICC, including its head of state.

However Sudan has already failed to arrest and transfer two other suspects sought by the Court, and there is little reason to expect that al-Bashir will voluntarily surrender. If Sudan fails to meet its obligations, the Court can refer the case of non-compliance back to the Security Council who may decide to take further measures.

Arrest and Transfer by States Parties to the Rome Statute

In general, State parties are obliged to comply with a request by the Court for surrender or assistance if a person the subject of an arrest warrant is found on their territory.

However the ICC Statute also provides, in Article 98(1) that the Court cannot make a request for surrender or assistance if it would require the requested State to breach its obligations under customary international law with respect to State or diplomatic immunity. This provision is designed to avoid any tension between requests from the Court, with which States Parties are obliged to comply, and international laws providing immunity from national proceedings for officials of a third state.

It would appear at first glance that this provision conflicts with Article 27. However Article 27 is concerned with the question of the Court’s jurisdiction, whereas Article 98 is concerned with international co-operation and judicial assistance. It is possible that the Court might have jurisdiction over an individual head of state, but that the same individual would have immunity from the proceedings in national courts involved in any attempt to arrest and transfer him.

According to the most common interpretation, the combined effect of the two provisions is that a State Party may not claim immunity for its own officials, but it must respect the immunity of the officials of a non-State Party. The Court can therefore only require States Parties to arrest and transfer officials of another State Party, since that other state would have forfeited the right to claim immunity for its officials, as part of its obligation to cooperate with the ICC under the Rome Statute.

If this interpretation is correct (it has not yet been tested before any court), then the crucial question regarding the possible arrest of al-Bashir by a State Party is whether the Security Council, in referring the situation in Darfur to the ICC, imposed on Sudan by implication all the obligations of a State Party to the Court. This is most likely what the Court would claim, in line with its argument that the ICC’s statutory framework as a whole should be applied

Arrest and Transfer by Non-State Parties

The Court can make a request for assistance of non-parties; however since they are not bound by the Court’s Statute, non-parties are not obliged to comply.

Nor did the Security Council, in Resolution 1593, impose a legal obligation on non- parties – other than Sudan – to cooperate with the Court. Instead, the Resolution said merely that the Security Council ‘urges’ non- parties to co-operate, wording that fell short of imposing an obligation.

Therefore, there is no obligation on a non-party state to attempt to execute the arrest warrant and transfer al-Bashir to the ICC, if he ventures onto that state’s territory. But that does not prevent the Court from asking from cooperation. Might then a non-party, if it so wished, choose voluntarily to arrest al-Bashir and transfer him to the ICC?

On the one hand, it might seem incongruous that a voluntary decision to cooperate with the ICC should override the established principle of sovereign immunity. On the other hand, it could be argued that what counts is whether Sudan is obliged by the Security Council resolution to waive any claims of immunity with respect to proceedings connected to the ICC.

As mentioned above in relation to Sudan’s obligations, one of the considerations that formed the basis of the Court’s decision to issue an arrest warrant was that the Security Council - by referring the Darfur situation to the Court - decided that the investigation and prosecution shall take place in accordance with the statutory framework of the Rome Statute.

Therefore, assuming this is correct, it should not matter whether the state that is seeking to arrest al-Bashir is itself a party to the Court or not—the right to arrest without regard to al-Bashir’s official capacity is based on an obligation that Sudan incurred vis-a-vis the ICC when the Security Council implicitly applied the Court’s Statute to it.

So there may be a possibility even for non-party states to arrest and transfer al-Bashir if they wish to. But it should be emphasized that the question of his immunity, both with respect to States Parties and non-parties, is something of a legal grey area, and there would certainly be grounds for him to contest any proceedings against him in either case.

The Removal of the Genocide Charges

The spokeswoman for the court in The Hague, Laurence Blairon, said Mr Bashir was suspected of being criminally responsible for “murdering, exterminating, raping, torturing and forcibly transferring large numbers of civilians and pillaging their property.” She said the violence in Darfur was the result of a common plan organised at the highest level of the Sudanese government, but that there was no evidence of genocidal intent, thus the 3 genocide charges were removed from the indictment. The Court upheld 7 counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes allegedly committed during the course of a counter-insurgency campaign against armed groups such as the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army and the Justice and Equality Movement, who are opposed to the Sudanese Government.

Under Article 6 of the Rome Statute, “genocide” means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

In order for an accused to be found guilty of genocide, it must be shown that, not only was he criminally responsible for one or more of the enumerated acts, but that he did so with the intent to destroy a group, in this case, the Prosecution alleged that al-Bashir had the intent to destroy the Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa groups of the Darfur region.

Pursuant to Article 58(1) of the Rome Statute, to obtain an arrest warrant the prosecution had to prove that there were ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing that the person in question committed the crimes in the indictment.

The Court stated that “if the existence of a [suspect’s] genocidal intent is only one of several reasonable conclusions available on the materials provided by the Prosecution, the Prosecution Application in relation to genocide must be rejected as the evidentiary standard provided for in article 58 of the Statute would not have been met.” This seems to indicate that in fact, the PTC applied the higher, “beyond reasonable doubt” standard, which among other things, would require in this case that a finding of the existence of genocidal intent is ‘the only inference available on the evidence.’ That is, the existence of other reasonable inferences – as the Court seems to affirm - would mean that this standard has not been met. However the standard of ‘reasonable grounds’ requires a different analysis, and is a much lower standard than that of ‘beyond reasonable doubt.’

Rejecting the decision of the Court that the Prosecution had failed to prove the existence of reasonable grounds that al-Bashir intended to commit genocide, ICC Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo appealed the decision on March 13. He referred in his application to the Genocide Convention, saying that genocide could also be defined as ‘dictating living circumstances to a particular group’ with the intention to destroy that group in whole or in part.

“Omar al-Bashir’s destiny is to face justice,” Moreno-Ocampo said following the Court’s decision. “What is happening in Darfur is that 2.5 million people are dying slowly in the camps … 5,000 are dying each month. It is time to protect the victims, it is time to stop bombing civilians, it is time to stop the rapes, it is time to stop the crimes.”

Related Links:

Who is Obliged to Arrest Bashir?

By Dapo Akande

EJIL: Talk!, March 13, 2009

Warrant of Arrest for Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir (PDF)

International Criminal Court

March 4, 2008

UN Security Council Resolution 1593 (2005)

United Nations

March 31, 2005

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

International Criminal Court

The ICC, Bashir, and the Immunity of Heads of State

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir attends a graduation ceremony at an air force academy near Khartoum, Sudan, Wednesday, March 4, 2009. Sudan denounced an international tribunal that issued an arrest warrant against its president Wednesday on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, calling it a "white man's court" that aims to destabilize the country. (AP Photo/Abd Raouf)

By Anthony Dworkin and Katherine Iliopoulos

The International Criminal Court announced on March 4, 2009 that it was issuing an arrest warrant against Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir for masterminding a campaign of crimes against humanity and war crimes by government troops and Arab militias in the Darfur region. The announcement, coming eight months after the Court’s prosecutor requested an arrest warrant, marks the first time that the ICC has sought the arrest of a sitting head of state. The Court decided not to proceed with the charges of genocide, ruling that there did not exist reasonable grounds upon which a finding could be made that al-Bashir had the necessary genocidal intent.

Following the announcement, al-Bashir suspended the operation of 13 aid organizations in Sudan, saying they had cooperated with the ICC by supplying information. He later said that he wanted all foreign aid organizations to leave within a year. The ICC’s announcement and the Sudanese response have generated much debate, but there has been comparatively little discussion about how al-Bashir might be delivered to the Court.

The Arrest Warrant and the Personal Immunity of Incumbent Heads of State

Announcing its decision to issue an arrest warrant, the Court’s Pre-Trial Chamber I asked the Court’s registrar to prepare a request for cooperation for President al-Bashir’s arrest and transmit it to Sudan, to all States Parties to the Rome Statute, to all United Nations Security Council members that are not party to the Statute, and to any other State as may be necessary. The Registrar duly prepared communications to Sudan, the States Parties, and to those members of the Security Council not party to the Statute. Presumably it is keeping open the option of sending a communication to any other state if the need arises.

Welcoming the announcement, the Court’s Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo said that Sudan was obliged under international law to execute the warrant of arrest on its territory, and that “as soon as Omar al-Bashir travels through international air space, he can be arrested.”

However the question of al-Bashir’s arrest may be more complicated than the Court’s requests and the prosecutor’s statement suggest, because of his position as Sudan’s head of state.

Under international law, the doctrine of sovereign or diplomatic immunity means that certain holders of high-ranking office in a State such as the Head of State enjoy immunities from jurisdiction in other States, both civil and criminal. That means that national courts are unable to try a high official of another state who is suspected of committing crimes - no matter how serious - as this would constitute a violation of state sovereignty. The United Nations is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all member states, whereby a state is not permitted to interfere in affairs that are within the domestic jurisdiction of another state. Sovereign immunity covers both a head of state and the state itself. Personal immunity only extends to incumbent heads of state; in the case of DRC v Belgium, the International Court of Justice said this was necessary in order for the head of state to be able to exercise his functions effectively.

There is little question that al-Bashir could be prosecuted before the ICC. According to Pre-Trial Chamber I, “al-Bashir’s official capacity as a sitting Head of State does not exclude his criminal responsibility, nor does it grant him immunity against prosecution before the ICC.” There are many precedents for international courts issuing indictments against sitting heads of state, and Article 27 of the Rome Statute of the ICC explicitly provides that the Statute applies equally to all persons without distinction based on their official capacity.

However the ICC does not have its own police force, and the Security Council has not authorized any international force to arrest him. He is only likely to face justice if he is arrested and transferred to the Court by the authorities of a State. Could a State do so without violating its legal obligation to respect his immunity as head of state?

Arrest and Surrender by Sudan

Sudan signed the Rome Statute in 2000 but has not yet ratified it. However the UN Security Council, in Resolution 1593 (2005) referred the situation in Darfur to the ICC Prosecutor, thereby granting the ICC jurisdiction over the matter.

In granting jurisdiction, the Security Council could be assumed to have also applied the provision in the Rome Statute that overrides any claim of immunity for heads of state. (This was the view taken by the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber, which said that the Security Council had accepted that investigations and prosecutions from Darfur “will take place in accordance with the statutory framework provided for in the Statute, the Elements of Crimes and the Rules as a whole.”) Even if the Security Council did not by implication apply this provision, there is arguably no immunity of heads of state from prosecution before international tribunals under customary international law.

The Resolution was passed under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, which gives the force of international law to Security Council resolutions concerning the maintenance of international peace and security. Paragraph 2 of Resolution 1593 says that the Security Council “Decides that the Government of Sudan and all other parties to the conflict in Darfur shall cooperate fully with and provide any necessary assistance to the Court and the Prosecutor.” Therefore Sudan has an obligation under international law to surrender anyone sought by the ICC, including its head of state.

However Sudan has already failed to arrest and transfer two other suspects sought by the Court, and there is little reason to expect that al-Bashir will voluntarily surrender. If Sudan fails to meet its obligations, the Court can refer the case of non-compliance back to the Security Council who may decide to take further measures.

Arrest and Transfer by States Parties to the Rome Statute

In general, State parties are obliged to comply with a request by the Court for surrender or assistance if a person the subject of an arrest warrant is found on their territory.

However the ICC Statute also provides, in Article 98(1) that the Court cannot make a request for surrender or assistance if it would require the requested State to breach its obligations under customary international law with respect to State or diplomatic immunity. This provision is designed to avoid any tension between requests from the Court, with which States Parties are obliged to comply, and international laws providing immunity from national proceedings for officials of a third state.

It would appear at first glance that this provision conflicts with Article 27. However Article 27 is concerned with the question of the Court’s jurisdiction, whereas Article 98 is concerned with international co-operation and judicial assistance. It is possible that the Court might have jurisdiction over an individual head of state, but that the same individual would have immunity from the proceedings in national courts involved in any attempt to arrest and transfer him.

According to the most common interpretation, the combined effect of the two provisions is that a State Party may not claim immunity for its own officials, but it must respect the immunity of the officials of a non-State Party. The Court can therefore only require States Parties to arrest and transfer officials of another State Party, since that other state would have forfeited the right to claim immunity for its officials, as part of its obligation to cooperate with the ICC under the Rome Statute.

If this interpretation is correct (it has not yet been tested before any court), then the crucial question regarding the possible arrest of al-Bashir by a State Party is whether the Security Council, in referring the situation in Darfur to the ICC, imposed on Sudan by implication all the obligations of a State Party to the Court. This is most likely what the Court would claim, in line with its argument that the ICC’s statutory framework as a whole should be applied

Arrest and Transfer by Non-State Parties

The Court can make a request for assistance of non-parties; however since they are not bound by the Court’s Statute, non-parties are not obliged to comply.

Nor did the Security Council, in Resolution 1593, impose a legal obligation on non- parties – other than Sudan – to cooperate with the Court. Instead, the Resolution said merely that the Security Council ‘urges’ non- parties to co-operate, wording that fell short of imposing an obligation.

Therefore, there is no obligation on a non-party state to attempt to execute the arrest warrant and transfer al-Bashir to the ICC, if he ventures onto that state’s territory. But that does not prevent the Court from asking from cooperation. Might then a non-party, if it so wished, choose voluntarily to arrest al-Bashir and transfer him to the ICC?

On the one hand, it might seem incongruous that a voluntary decision to cooperate with the ICC should override the established principle of sovereign immunity. On the other hand, it could be argued that what counts is whether Sudan is obliged by the Security Council resolution to waive any claims of immunity with respect to proceedings connected to the ICC.

As mentioned above in relation to Sudan’s obligations, one of the considerations that formed the basis of the Court’s decision to issue an arrest warrant was that the Security Council - by referring the Darfur situation to the Court - decided that the investigation and prosecution shall take place in accordance with the statutory framework of the Rome Statute.

Therefore, assuming this is correct, it should not matter whether the state that is seeking to arrest al-Bashir is itself a party to the Court or not—the right to arrest without regard to al-Bashir’s official capacity is based on an obligation that Sudan incurred vis-a-vis the ICC when the Security Council implicitly applied the Court’s Statute to it.

So there may be a possibility even for non-party states to arrest and transfer al-Bashir if they wish to. But it should be emphasized that the question of his immunity, both with respect to States Parties and non-parties, is something of a legal grey area, and there would certainly be grounds for him to contest any proceedings against him in either case.

The Removal of the Genocide Charges

The spokeswoman for the court in The Hague, Laurence Blairon, said Mr Bashir was suspected of being criminally responsible for “murdering, exterminating, raping, torturing and forcibly transferring large numbers of civilians and pillaging their property.” She said the violence in Darfur was the result of a common plan organised at the highest level of the Sudanese government, but that there was no evidence of genocidal intent, thus the 3 genocide charges were removed from the indictment. The Court upheld 7 counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes allegedly committed during the course of a counter-insurgency campaign against armed groups such as the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army and the Justice and Equality Movement, who are opposed to the Sudanese Government.

Under Article 6 of the Rome Statute, “genocide” means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

In order for an accused to be found guilty of genocide, it must be shown that, not only was he criminally responsible for one or more of the enumerated acts, but that he did so with the intent to destroy a group, in this case, the Prosecution alleged that al-Bashir had the intent to destroy the Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa groups of the Darfur region.

Pursuant to Article 58(1) of the Rome Statute, to obtain an arrest warrant the prosecution had to prove that there were ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing that the person in question committed the crimes in the indictment.

The Court stated that “if the existence of a [suspect’s] genocidal intent is only one of several reasonable conclusions available on the materials provided by the Prosecution, the Prosecution Application in relation to genocide must be rejected as the evidentiary standard provided for in article 58 of the Statute would not have been met.” This seems to indicate that in fact, the PTC applied the higher, “beyond reasonable doubt” standard, which among other things, would require in this case that a finding of the existence of genocidal intent is ‘the only inference available on the evidence.’ That is, the existence of other reasonable inferences – as the Court seems to affirm - would mean that this standard has not been met. However the standard of ‘reasonable grounds’ requires a different analysis, and is a much lower standard than that of ‘beyond reasonable doubt.’

Rejecting the decision of the Court that the Prosecution had failed to prove the existence of reasonable grounds that al-Bashir intended to commit genocide, ICC Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo appealed the decision on March 13. He referred in his application to the Genocide Convention, saying that genocide could also be defined as ‘dictating living circumstances to a particular group’ with the intention to destroy that group in whole or in part.

“Omar al-Bashir’s destiny is to face justice,” Moreno-Ocampo said following the Court’s decision. “What is happening in Darfur is that 2.5 million people are dying slowly in the camps … 5,000 are dying each month. It is time to protect the victims, it is time to stop bombing civilians, it is time to stop the rapes, it is time to stop the crimes.”

Related Links:

Who is Obliged to Arrest Bashir?

By Dapo Akande

EJIL: Talk!, March 13, 2009

Warrant of Arrest for Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir (PDF)

International Criminal Court

March 4, 2008

UN Security Council Resolution 1593 (2005)

United Nations

March 31, 2005

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

International Criminal Court

Related posts: