|

Things

As They Are -- Photojournalism in Context Since 1955

By

Mary Panzer, with an afterword by Christian Caujolle

World

Press Photo, Amsterdam, and Chris Boot Ltd., London, 2005

Reviewed

by Francis Hodgson

World

Press Photo is a charity which exists to promote photojournalism,

principally by an annual competition and touring exhibition.

At any time in the last thirty years there have been good

reasons to fear for the future of photojournalism.

First television, then the internet threatened the magazines

around which the trade had centred. The digital revolution,

first in image distribution, then in image capture, presented

(and still presents) another huge worry. This book

ends with a glance at the way that camera-phone pictures

by amateurs make the front pages in cases like the Indian

Ocean tsunami. (The specifically British example would

be the underground bombings of July last year.) Professional

photographers get around the world with astonishing speed

but every western citizen now carries a camera in his pocket

and knows enough about the media to make its pictures available

for publication within an e-mail or two. It is easy to see

how the professionals might tremble for their livelihood.

There

are other worries. Photojournalism used to be the

flower of photography, and often the flower of journalism,

too. Editors have less money for big newsy photographic

projects, now, and photographers have to look for funding

elsewhere. It is in the art world that photography

is the driving force, and the medium of choice. In

journalism it is now just one ingredient of the digital

soup. Further, the conditions of distribution have been

so radically altered by the growth and aggregation of the

picture libraries that the independence of the photographers

and of the small agencies through which they used to work

is seriously in doubt. A note of slightly nervous nostalgia

in this book is understandable. It should so obviously

have been called Things As They Were, for the industry will

never be the same again. Yet it is not too late to understand

the practical and ethical issues which photojournalism has

already confronted. It’s not going to disappear,

even if the conditions in which it operates are changing

faster than anybody might have predicted.

|

|

|

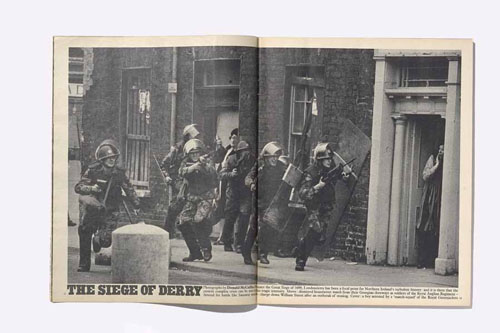

Don

McCullin ‘Siege of Derry - dismayed housewives watch

as soldiers of the Royal Anglian Regiment charge down William

Street after an outbreak of stoning’, published in

the Sunday Times Magazine (UK), 1971

Photograph

© Don McCullin |

|

|

The

specificity of this book is that the pictures and the stories

in which they were grouped are presented as they were originally

seen, with whole magazine pages including text and headlines

overlaid or alongside. This capitalizes, no doubt perfectly

deliberately, on the present mania for “design”.

By presenting pretty layouts (and many are more than that,

good examples of the perpetually engrossing waltz between

space and pictures and text) the book takes some of the

heat out of the pictures. But at what point does a

well designed and copiously illustrated book like this become

“coffee-table”? And if even the suggestion of

triviality or superficiality is possible, what does that

make of the subjects of the photographs? In this book, as

always, the relations between photography and reality are

uncomfortable, difficult. It is hard to escape that old

familiar feeling that great suffering, great injustice,

great squalor and anger and pain have been a little too

easy to render on coated paper.

Reproducing

original layouts entire is awkward. It implies the

restoration of the original teams: writers, graphic designers,

editors and picture editors, are all as important in a full

layout as the photographers. The pictures are put forward

here as elements for editors and designers to use, which

in the real world they certainly were. But no proper credits

are consistently given to the designers and the reproduced

text is normally too small to read. The book thus

silently perpetuates the romantic concentration on the photojournalist

as an individual perhaps more free in his movements than

he has ever really been.

|

|

|

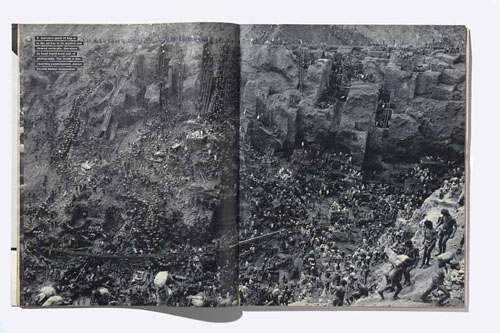

Sebastião

Salgado ‘Serra Pelada – A barranco

(plot) of 6sq m in the pit has to be worked and cleared

vertically, therefore by hand. The result is this swarming

pandemonium, almost beyond human imagination’, published

in the Sunday Times Magazine (UK), 1987

Photographs

© Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images

/ nbpictures |

|

But

of course that is one strand of the story. However

much one looks at photojournalism as a sub-branch of the

modern media industries or modern visual culture, it is

hard to escape the extraordinary people at its heart.

Alfred Eisenstaedt, asked in the BBC series The Master Photographers

how he felt photographing Hitler, answered for the whole

profession: “When I have a camera in my hand, I know

no fear.”

This

is not specially or even mainly a book of war photographs.

It has its share of them, however, and puts them in a thought-provoking

context. The editors are sensitive enough to deal

well with possible charges like Western centredness, or

of magazines being far from neutral arenas. They are

clear in what they are concentrating upon: connected series

of pictures not individual images, and images published

mainly in magazines. Here is Don McCullin’s

report from Derry for the Sunday Times in 1971, brilliant

picture after brilliant picture. A squad of howling

soldiers charges past two doorways in which civilian ladies

take the only cover they can find. A pale bollard

in the left half balances the pale doorway on the right.

The movement is so wholly from left to right that even the

cowering ladies lean that way, as though blown over by the

wind-wake of the rushing soldiers. McCullin saw black soldiers

fighting white civilians, a shocking reversal of the colonial

norm. And we would all get used, in time, to his portrayal

of conflict as white against white. It takes an effort,

even in front of the magazine spreads reproduced, to remember

just how shocking this was. Photography would never be able

to analyse, for example, the failure of local government

in Northern Ireland in great detail. But nobody could see

these pictures in London and think that there was just a

little civil disorder going on over the sea.

The

focus upon magazines may have been a mistake. It looks better

in the early years of this overview than it does at the

end. So many photographers now regard the book as

the proper complete expression of their work, and magazine

publication only as a necessary intermediary stage, that

the story is somewhat falsified by concentrating on the

old-fashioned model of publishing. By what standard, for

example, can one consider Robert Frank’s fundamental

book, The Americans (published right at the beginning

of the period covered here, in 1958) not to be photojournalism?

|

|

|

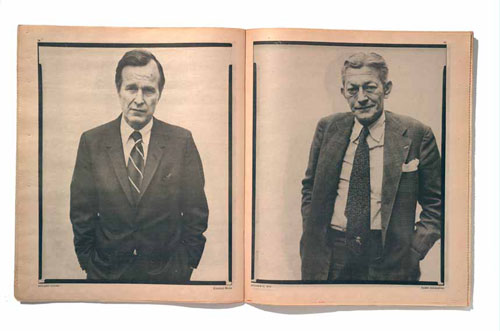

Richard

Avedon ‘The Family – George Bush and James Angleton’,

published in Rolling Stone (USA), 1976

Photographs

© Richard Avedon |

|

On the other hand, many might be surpised by the inclusion

of Richard Avedon’s 1976 issue of Rolling Stone with

its dozens of apparently plain straight portraits on a white

ground of the American political establishment. My

own view is that this broader, more inclusive view is important

and interesting: too many views of photojournalism shy away

from the plain fact that looking with burning critical interest

at the world need not necessarily mean looking only at gore.

Here we have also Bruce Weber’s astonishing series

of the US Olympic team before the Los Angeles Games of 1984.

The hero-worshipping point of view is quite openly derived

from Leni Riefenstahl’s photography of the Olympians

of the Nazi games in 1936. The camera is lower than

the athletes, who are seen in the kind of luscious mid-tones

deliberately conceived to render muscle. Yet Weber managed

to query his own make-believe by the simplest means of all.

The tarpaulin backdrop of his mobile studio is in almost

every shot. It is partly a grubby theatre curtain, but it

is also a quote from the crude illusions of nineteenth century

portrait studios. The camera may always tell the truth,

these pictures say, but whose truth and which truth is not

always so plain. That’s a salutary thought to bear

in mind perhaps particularly in front of war photography.

This

book, perhaps inevitably, makes too many arbitrary judgments

of what’s in or out to count as a critical history,

yet it is plainly an honourable and serious book with ambitions

above the coffee-table. That it struggles to situate

itself naturally may be its undoing. Both journalism and

photography used to be mainly learnt in the doing.

Navigating the precarious reefs of technique, of law, of

ethics and opportunity and marketing was done by the seat

of the pants. But each discipline now has a large

and serious academic and semi-academic hinterland.

It is asking for trouble to step back from the red-hot immediacy

of photojournalism in process without fully moving to a

cool concentration of dispassionate analysis. In the

end, this is an exhilarating tale of photographic knights-errant

on quest, and a good-looking collection of some hundred

and twenty picture stories, but it skirts more issues than

it covers in depth.

Francis

Hodgson, who is based in London, writes regularly on photography

for the Financial Times and other publications.

Things

As They Are - Photojournalism in Context Since 1955

by Mary Panzer is published by Chris Boot in association

with World Press Photo, price £45.00

Book

available with 30% discount on www.chrisboot.com

|

|

|