| October 29, 2004 | ||

|

Three Misconceptions about the Laws of War By

Jelena Pejic |

||

|

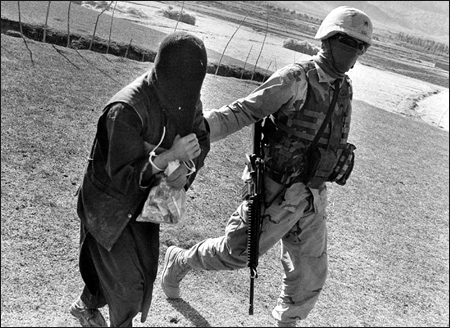

After decades of being debated among the initiated few, the basic concepts of the laws of war seem finally to have captured the public's attention. The rights of prisoners of war, the meaning of humane treatment and the duties of occupying powers are just some of the issues currently being discussed at both international conferences and dinner tables. The bright spotlight directed at international humanitarian law (the preferred designation for the laws of war) is welcome news for those who care about the protection of persons affected by armed conflict. However, there is also a risk of interpretations that do not take into account the delicate balance between state security and individual rights that underlies this body of rules. Outlined below are three examples:

1. The existence of a global "war on terrorism". While the term "war on terrorism" is so much a part of daily parlance that one hardly gives it a second thought, it must be asked whether this "war" is an armed conflict in the legal sense. The short answer is no. Only certain aspects of the "war on terrorism" are in fact war. Under the 1949 Geneva Conventions (please note the plural!) international wars are those fought between states. The 2001 war between the US-led coalition and the then effective government of Afghanistan, waged as part of the "war on terrorism", was an example of an international armed conflict. Humanitarian law does not envisage an international war between states and non-state armed groups for the simple reason that states have never been willing to accord armed groups the privileges enjoyed by members of regular armies. To say that we are witnessing a global international war against groups such as Al-Qaeda would mean that under the laws of war their followers would be equal in rights and obligations to members of regular armed forces. It was clear back in 1949 that no country was prepared to contemplate exempting non-state fighters from criminal prosecution for lawful acts of war, which is the crux of prisoner of war (POW) status. The Geneva Conventions, which grant such status under strictly specified conditions, are thus neither "outdated" nor "quaint"; their drafters were fully aware of the political and practical realities of international armed conflict and crafted the treaty provisions accordingly. The "war on terrorism" can also take the form of a non-international armed conflict, such as the one currently being waged in parts of Afghanistan between the current Afghan government, supported by allied states, and different armed groups including remnants of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. This conflict is non-international because it is being carried out with the consent and support of the Afghan government and does not involve two opposed states. The ongoing hostilities in Afghanistan are thus governed by humanitarian law rules applicable to non-international armed conflicts, found in both treaty and customary humanitarian law. The same body of rules would apply in other similar circumstances where a definable non-state group is party to the armed conflict and where the level of violence has reached that of an armed conflict. The critical question that generates the most confusion is whether the totality of acts of terrorism carried out in various parts of the world (outside of situations of armed conflict such as Afghanistan) constitute one and the same armed conflict in the legal sense. Can it be said that the recent school massacre in Beslan, the conflict in Israel/Palestine and the bombings in Bali, Turkey or Madrid, can be attributed to one and the same party? Can it, in addition, be claimed that the level of violence involved in each of those places has reached that of armed conflict? On both counts, it would appear not. The Spanish authorities did not, for example, apply conduct of hostilities rules to deal with the Madrid train bombing suspects. Those rules would have allowed them to factor possible incidental civilian deaths ("collateral damage") into their calculation of how to deal with the suspects. Instead, they applied the rules of law enforcement. They attempted to capture the suspects for later trial and took care to evacuate nearby buildings in order to avoid all injury to persons living in the vicinity. In sum, each situation of organized armed violence must be examined in the specific context in which it takes place and be legally qualified either as war or not, depending on the factual circumstances. A global "war on terrorism" might be a useful rhetorical device, but it does not reflect the reality or the variety of responses to terrorist acts on the ground. The laws of war were tailored for war. It serves neither the aims of state security nor of individual protection to extend them to situations short of armed conflict. 2. "Unlawful combatants" have minimal (or no) rights. The launching of the global "war on terrorism" also launched the term "unlawful combatant" into the public discourse, raising much controversy about the rights of such persons. To begin with, combatant status exists only in international armed conflict and humanitarian law treaties contain no explicit reference to "unlawful combatants". This designation is shorthand for persons who directly participate in hostilities without being members of the regular armed forces, which, events have proven, often happens in both international and non-international armed conflicts. Contrary to some assertions, international humanitarian law does provide for measures that can lawfully be taken with regard to "unlawful combatants". “Unlawful combatants” may be attacked during the time that they are directly participating in hostilities. If captured, they may be criminally prosecuted under domestic law for the act of taking up arms, even if they have fought according to the laws of war. They may also be detained for security reasons until the end of active hostilities, unless released earlier. In specific circumstances and within certain bounds, they may even be denied some of the privileges of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Under humanitarian law no one who has been detained, including an "unlawful combatant," may in any way be subjected to acts prohibited by the Conventions such as murder, violence to life and person, torture or inhumane treatment, or outrages upon personal dignity; nor may they be denied the right to a fair trial. "Unlawful combatants" are in this sense fully protected by humanitarian law. It is simply misleading to suggest that they have minimal or no rights. One of the purposes of the laws of war is to protect the life, health and dignity of all persons affected by armed conflict. It is inconceivable that calling someone an "unlawful combatant" should suffice to deprive him or her of rights guaranteed to every individual. 3. Different rules of interrogation for different detainees. There is only one set of rules for the interrogation of persons detained in an international armed conflict regardless of whether they are POWs or civilians (including "unlawful combatants"). The Third Geneva Convention does provide that POWs cannot be coerced to answer questions beyond giving their name, rank, date of birth and service number. This was done primarily in order to prevent the detaining power from eliciting information on ongoing military operations from POWs right after capture. There is, however, nothing in the Convention that would for, example, prohibit the interrogation of a POW suspected of war crimes.

The key issue is therefore not, "Can a detainee be interrogated?" but, rather, what means may be used in the process. Neither a POW nor any other person protected by humanitarian law can be subjected - it bears repeating - to any form of violence, torture, inhumane treatment or outrages upon personal dignity. These acts, and others, are strictly prohibited by international law, including humanitarian law. Under the laws of war it is the detaining authority that bears full responsibility for ensuring that no interrogation method crosses the line.

Jelena Pejic is a Legal Adviser in the Legal Division of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The Crimes of War Project will continue to publish articles about the legal status of the U.S. military campaign against al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups. We welcome responses or submissions from our readers – please send them to the editor at [email protected].

Related Chapters from the Book:

Related Links:

International Committee of the Red Cross

|

||

This site © Crimes of War Project 1999-2004 |

|