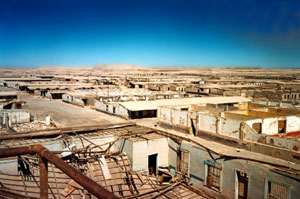

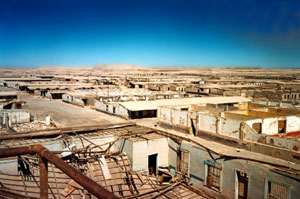

Overview

of Chacabuco, the abandoned mining town in Chile's northern

desert, used by the military as a concentration camp for political

prisoners during the early years of the dictatorship.

Photo Copyright © Joanne Pottlitzer, 1995 |

Those

1,000 days [of Allende’s Popular Unity government] seemed like

one single day, one single day and one single night -- until September

11. All that had been elation, street parties, dance, murals of

that time became overshadowed by another reality, like a magnificent

sunny day that suddenly begins to cloud over, and there is a horrible

storm.

From

September 14, 1973, until the middle of 1974, I was held prisoner

in different jails. I was at the National Stadium until they closed

it on November 9 [1973], and in Chacabuco for six months. A next-door

neighbor turned me in. But I knew they had to find me sooner or

later. I think there were two people the military wanted to use

as examples: Victor and me. That day [September 11] Victor was at

the Technical University, and that very day they arrested him. I

fell three days later. I’ve always said, very seriously, that

I’m alive thanks to the death of Victor. It was about who they

got first, who to use as an example: "This is what happens

to little singers for getting involved in politics." My experience

in the National Stadium is very painful -- I have it repressed.

One day I’ll get it out. Maybe the most important thing that

can be said is that once we were in prison, and everyone knew that

we were there, we developed a cultural program inside the jails

of Chile, an enormous program. There were hundreds of cultural agitators

in prison. There came a time when it was much more to the dictatorship’s

advantage to send us abroad than to keep us in the jails, because

we were making more noise inside than outside.

In Chacabuco, the camp in the north, we lived in pavilions, houses

that had belonged to the nitrate mining town of Chacabuco when the

English were there at the beginning of the 20th century. When copper

replaced nitrate as our principal export, the mine and the houses

were eventually abandoned. (Salvador Allende had decided to make

that mining town into the first national monument to the working

class. He got as far as inaugurating it, and then workers ended

up there as prisoners, along with artists.) There were two rooms,

a small patio and a hot plate where we prepared our meals. The houses

had no roofs. We covered them with canvas. We covered doors and

windows with arpilleras [The patchwork craft done by women

who participated in workshops created in early 1974 by the Pro Peace

Committee to relieve their tensions and anxieties. The women were

usually from working-class neighborhoods; their husbands, partners,

sons or fathers had lost their jobs or had been detained and disappeared].

I remember Gonzalo Palta, an actor who was a fellow prisoner there,

directed one of the theater groups in Chacabuco. A young man who

had directed a chorus in the Communist Youth organization mounted

a chorale with more than 400 prisoners. We created mural newspapers.

There were many journalists in the jails and excellent illustrators

and caricaturists, so we didn’t need photographers -- besides,

we didn’t have cameras. They drew with pencils. Once it was

known that you were in prison, we could receive packages from outside,

with food, with books, with materials to write with. Some of us

wrote poetry while we were there.

|

|