| October 2004 How

to Intervene in Africa’s Wars |

||||||

|

In the last decade questions about the effectiveness and morality of outside intervention in internal conflict - particularly when gross violations of human rights are taking place - have risen to the top of the international agenda. In Africa, where conflict has been widespread and frequently accompanied by massive harm to civilians, the dilemmas associated with intervention appear in a particularly pointed form. Since the early 1990s a wide variety of different approaches have been tried - ranging from the United Nations’ inconclusive role in Somalia, through the ongoing, drawn-out peace industry in Central Africa, and more recently the British and French interventions in Sierra Leone and Cote d’Ivoire. What conclusions can we draw from this varied history about the value of external military action as a way of resolving conflict or mitigating its worst effects?

The International Context Among those who endorse the principle of humanitarian intervention, a broad consensus had emerged by 2001 on the rules that ought to govern it. These were laid out in the Report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, The Responsibility to Protect. In essence, they required that the threshold for outside intervention should be a grave breach of humanitarian law such as genocide or ethnic cleansing, that military intervention should always be a last resort, and that any intervention must command the support of regional opinion and obtain multilateral authorisation. The contemporary challenge for the United Nations, as the vehicle for such intervention, is whether it can develop the rules and procedures (and cultivate the necessary political will) for effective action. The context for intervention was changed significantly by the events of September 11 and the effect they have had on US foreign policy and resolve. At least for the moment, these events appear to have reversed the US tendency towards isolation and given rise to a desire to deal proactively (and pre-emptively) with threats, including those arising from undemocratic or failing states, before they can have a direct impact on the United States. This change of outlook was set out in the US National Security Strategy published in September 2002 and is routinely expressed by US policy-makers. As Vice-President Dick Cheney put it at the World Economic Forum in January 2004, the United States “must confront the ideologies of violence at source by promoting democracy throughout the Middle East and beyond.”1 September 11 has elevated the importance of weak or collapsed states in the international community and increased the urgency of efforts to deal with them.

At the same time, the wars in Afghanistan and in Iraq have posed a number of fundamental challenges to the emerging philosophy and practice of intervention. In philosophical terms, as United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan put it, Iraq represented a “challenge to the principles on which, however imperfectly, world peace and stability have rested for the last fifty-eight years” and could set precedents that would result “in a proliferation of the unilateral and lawless use of force.” Annan warned against following the “laws of the jungle” in the quest for global security.2 The US-doctrine of pre-emption raises serious questions about the United Nations’ relevance and modus operandi, though perhaps not as acutely now as a year ago in the full flush of apparent success in Afghanistan and Iraq. African States in Crisis Nevertheless, whatever the difficulties faced in Iraq and Afghanistan and the eventual political fate of the so-called ‘neo-imperialist’ or ‘neo-conservative’ thinkers in Washington, this should not distract attention from the conditions faced in many areas that are likely sites for conflict resolution or peace support attempts. These are weak, failing, failed, and poverty-stricken states - states exhibiting a fiction of sovereignty in the form of borders and seldom demonstrating a comparable reality of good governance, state authority and control, and responsibility towards their citizens. This is the actual nature of at least some African countries’ sovereignty and sets the background to any discussion of intervention on the continent. The long economic crisis that many African countries have experienced since the late-1970s has caused a profound erosion of their governments’ revenue bases. Even the most basic agents of the state - agricultural extension agents, tax collectors, census takers - are no longer to be found in many rural areas. Some states are increasingly unable to exercise physical control over their territories. The extremely limited revenue base of many African countries is also partially responsible for one of the most notable developments on the continent over the last thirty years: the change in the military balance between state and society. Whatever their other problems, African states at independence usually had control over the few weapons in their country. However, as states atrophy, their militaries and policing agencies also erode: readiness declines as there are no funds for training, equipment is no longer maintained, and many soldiers unpaid. At the same time, those who wish to challenge a government have been able to arm themselves, helped by the spill-over of armaments from conflicts throughout the region and by the cheap price of weaponry following the Cold War. These conditions will not alter regardless of who occupies the White House, at least not in the short-term. When Peace Building Works The experience of recent years has produced a body of evidence about the factors that contribute to successful conflict resolution and peace building efforts. These guidelines were summed up in the UN Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations, colloquially known as the ‘Brahimi Report’, which was published in 2000. A central point made in the Report was the need for mandates to specify an operation’s authority to use force. This might require bigger forces, better equipped and more costly but able to be a credible deterrent. In particular, UN forces for complex operations should have intelligence and other capabilities necessary to mount an effective defence against violent opposition. The Brahimi Report also recommended the incorporation of civilian police and other elements involved in the domestic rule of law, into peace operations. Finally, it emphasized the importance of making sure that missions were well led and attracted staff of uniformly high quality. The Brahimi Report reflected a growing awareness of a formula for successful conflict resolution and peace-building efforts, to which the experience of South Africa and West African countries contributed. Perhaps the primary lesson from South Africa’s own transition and its experience in African conflict mediation is that successful resolution of inter-communal problems depends on the need for communities to recognise the rewards of co-operating - and, conversely, the costs of not doing so. For conflict resolution to succeed there has to be a real basis for an internal settlement, where the parties want peace rather than war and compromise rather than continued conflict. A way has to be found in which the major conflicting parties can simultaneously achieve essential elements of what they want. If the settlement merely puts off the day of reckoning (as, for example, it did in Angola), then mediation efforts are not going to progress far or any agreement stick for a prolonged period of time. Solutions emerging in this way are more likely to result in a relatively peaceful transition, in which a critical mass of skills necessary for economic transition are retained (as in South Africa, for example) rather than scared away (as in Mozambique and Angola). Thus, importantly, there must be links between the population and the negotiators. Civil society can play an important role in creating this ‘middle-ground’, providing the wider framework which serves to urge leadership towards compromise as well as assisting in the development of democratic practices and institutions. At the same time, there must be a reasonably united international community, in which different outside parties can bring pressure on the rival domestic parties to settle. Apart from South Africa itself, the only post-Cold War case in which a negotiated solution to a Southern African conflict has thus far worked successfully is Mozambique. There, as in the transfer from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe in 1979, the amount of leverage that the external mediators could bring to bear on the domestic combatants was critical. The same could be said of the Namibian side of the Angolan-Namibian accords in 1988, which held, even if the Angolan part of that deal did not. By contrast, in the turbulent transition away from the rule of President Mobutu Sese Seko in the former Zaire in 1997, Washington and Paris had their own (sometimes competing) agendas. It was clear, too, that Southern African leaders also disagreed over what to do in Zaire. For successful conflict resolution, the external community must also offer the necessary resources, particularly in the post-conflict, peace-building phase. The provision of external facilitators or mediators may be important, but this should not obscure the importance of developing local talent. There is a need, in this regard, to distinguish between the use of prominent personalities as patrons of a peace process and the use of facilitators. There is a danger also of expecting external agencies to take up the job of government, whether by design (such as in Sierra Leone) or default (in Angola) through a reliance on humanitarian assistance. Domestically, trust-building and inclusivity are also vital in devising democratic solutions. There is, however, a need to make a clear distinction between the use of a government of national unity as a means to a political end, rather than as an end in itself. There are dangers in using inclusivity as a way to legitimate fraudulent elections and outcomes rather than as a conduit for reconciliation. Finally, elections should be seen as the end-point rather than the start of a process of democratisation. There is a need for a deepening of a ‘culture’ of democracy, beyond the creation of formal democracies through elections. Until this forms part of the essence of African polities, the potential for political reversal remains, as does the danger of programmes such as the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) faltering when elite and local political interests are threatened by the implementation and operation of international norms and standards. The setting and monitoring of such governance standards and establishment of such a culture has to be a bottom-up, civil society-oriented process, rather than one that is imposed from above. The Somali Example Since the collapse of the Siad Barre government in Somalia in 1991 and the ignominious withdrawal of UN troops from Mogadishu in 1995, there have been fourteen peace conferences involving various Somali factions, including those in Arta in Djibouti, Addis Ababa, Rome, and most recently Mbaghati near Nairobi. Meanwhile the number of warlord factions has increased from three in 1993 to around fifty a decade later. The Mbaghati talks had by the start of 2004 drifted on for more than a year, at an estimated cost of $7-8 million (funded principally by the European Union). Clan leaders were comfortably ensconced in luxurious residences, such as the ‘680 Hotel’ in central Nairobi, while facilitators puzzled about how to advance the talks. Progress at Mbaghati has been hindered by personal ambitions, notably the rivalry between Abdulahi Yusuf, the president of the Puntland territory within Somalia, and Abdilqasim Salad Hassan, the president of the Transitional National Government (TNG) established as a result of the Arta process. As Rakiah Omaar, an analyst for Africa Rights based in Somaliland, has observed, “Nairobi is a waste of time … reinforcing and giving legitimacy to the warlords by giving them a platform and visibility and allowing them to manipulate the situation.”3 Although by mid-2004 the talks, which started in October 2002, were apparently nearing conclusion, there remained doubts as to their viability in the absence from the negotiations of key factions including leaders from Somaliland along with the head of the Somali National Alliance Hussein Mohammed Aidid. Moreover, the objectives of appointing 275 new members of parliament, inaugurating a new Somali government and selecting a new Somali president appeared illusionary in the face of an oft-violated cease-fire. The Somali Republic had been formed out of a merger in 1960 between the former British Somaliland to the north, and Italian Somalia. This was supposed to be a first step in a pan-Somali dream including kin in Kenya (Northern Frontier District), Djibouti and the Ogaden region of Ethiopia. Somaliland was in fact an independent state for five days before this union, and the creation of the Somali Republic remained disputed by many in the north. They got their chance with the collapse of the Siad Barre government in January 1991, when Somaliland declared itself an independent republic. Since that time, Somalia has represented the best (and perhaps only) example of a collapsed state, where there is a complete absence of central authority. Somaliland, by comparison, has been left largely to its own devices and has successfully managed to emerge from the decades of devastation all on its own.

Somaliland is today an Islamic democracy in which traditionalist clan elements co-exist with democrats through the clan elder dominated Guurti upper house and the 82-member lower house. This hybrid political system was the product of several years of hard bargaining between the clans before peace was established throughout the territory in the mid 1990s. A 2001 referendum on a new constitution and the December 2002 local elections were followed by the staging of presidential elections on 14 April 2003, won by the incumbent Dahir Rayale Kahin with a majority of 80 votes out of half a million cast. Legislative elections are scheduled for 2005. This is tremendous progress by any developing country’s measure; the more so when compared to the failure of Somalia. Lacking international recognition, Somaliland has been left to its own devices in terms of finding its development feet. This has been immensely difficult for a country where tremendous economic challenges exist. As the UNDP head for Somaliland put it, “They have done it all on their own.”4 Foreign aid from international organisations and donors is constrained by Somaliland’s lack of international recognition. It amounts to perhaps $40 million per year, half of this from the UN and its various agencies. This offers little succour for a government whose annual budget is just $18.9 million and on which there are myriad demands of health, education, water and other soft and hard infrastructure issues. Nearly half of the current budget is consumed by salaries for the 15,000-strong police and military, a critical consideration in keeping the peace by keeping the militias in. The most important source of income is from remittances abroad, some $300 million annually. What does a comparison of the experiences of Somaliland and Somalia teach us about the value of external intervention? In this instance, it suggests that there are advantages to a peace process that is homegrown and not driven by foreign timetables and agendas.

This raises questions for situations elsewhere in Africa: would Zimbabwe be better off if the external and regional community left it alone? This means not only leaving it to its own devices in terms of political issues, but also not supporting humanitarian assistance. This could rapidly ratchet up the pressure, if not violence, for Mugabe’s removal, even though it is difficult to see the world refusing to provide food aid as images of starving Zimbabweans flood television screens. But in so doing, they are arguably killing more with their conscience, distorting the link of accountability between the government and the populace. What can African states do? Both South Africa and Nigeria have played an active role in regional peace support missions, the latter notably through ECOMOG - the armed monitoring group set up by the Economic Group of Western African States (ECOWAS) - in Liberia and Sierra Leone. In South Africa’s case, apart from the ill-conceived military intervention into Lesotho through Operation Boleas in September 1998, the peace support missions have been limited to sending observers to monitor the Ethiopian-Eritrean cease-fire and, more recently, detachments to Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In 2001, South Africa committed 700 troops to Burundi to protect politicians after former president Nelson Mandela and Deputy President Jacob Zuma brokered a peace settlement . By February 2004, this figure had increased to 1,520. The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) contingent was supposed to have been joined by others from Nigeria, Senegal and Ghana, but those three countries have been slow to meet their commitment and the African Mission in Burundi (AMIB) now includes detachments from Ethiopia and Mozambique. In January 2002, Zuma committed the SANDF forces to Burundi until their mission was “no longer necessary.”5 Some 98 SANDF soldiers were deployed in 2001 as part of MONUC (the UN peacekeeping mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo),6 while approximately 1,240 were deployed under MONUC III in 2003/4. In the 2003/4 budget statement, the South African government allocated R1.1 billion “to support peacekeeping operations.”7 While soldiers in Kinshasa and Bujumbura in Burundi tell stories of widespread acceptance by the local people wherever they go, a number of difficulties have been experienced.8 In the DRC, SANDF soldiers have privately questioned the relevance of their training, and in particular their “cultural preparation” for the environment. In Burundi, simply finding enough for the soldiers to do has been problematic. Overall, South Africa’s peacemaking and peacekeeping experience after 1994 illustrates the limits of its power even in its direct region. After all, it has been unable (or unwilling) to positively influence events in neighbouring Zimbabwe, and has experienced ongoing difficulties in the Congo, Burundi and even tiny Comores, in spite of the application of considerable diplomatic effort and resources. Part of the reason for this lack of results comes down to method: the reluctance to deviate from Pretoria’s policy of ‘quiet diplomacy’ over Zimbabwe and the equation of alternatives as either ‘megaphone diplomacy or military invasion’ is one example. But some of it relates to the difficulty in finding political and security solutions to what essentially are inter-related questions about state identity and economic conditions in problematic African states. In simple terms, at a minimum, do not expect any greater results from African-led intervention than those of non-African powers. There is also a belief, certainly among the diplomatic community resident in Africa, that a focus on key states will assist in resolving conflict. The need to stabilise Sudan and the DRC is often mentioned in this respect given their potential as African growth ‘poles’. However, the reality is rather that these states, far from being sources of dynamic regional integration, have long been reasons for regional insulation from their problems. The smaller states in Africa have done comparatively well in per capita GDP growth terms over the past two decades, while it is the larger states including Nigeria, the DRC, Ethiopia, Sudan and Angola, that have performed comparatively badly with a per capita GDP of under US$200 less than half the continental average.9 In addition, despite their advantages for growth, their sheer size and related complexity has made the idea of intervention daunting. The Need for Security Now that so many of the domestic and international supports for African states have disappeared, it was inevitable that some states would collapse. The contradiction of states with only incomplete control over their hinterlands but full claims to sovereignty was too fundamental to remain submerged for long. The turning point was when Yoweri Museveni took power in Uganda in January 1986. This was the first time that power had been seized in independent Africa by a leader who had gone back to the bush and formed his own army. It was a literal instance of the hinterland striking back. Previous military takeovers had originated in the national army and were essentially palace coups. Soon after, men in other countries who had a taste for power and (detected) grievances with which to mobilize followers found that there was an under-policed and incompletely controlled space in the rural areas where they could assemble a rebel force. As a result, since 1986, inspired, and sometimes supplied, by Museveni (who has attempted to remake his neighbourhood by force), armies created to compete against national forces in Rwanda, Zaire, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Congo-Brazzaville, and Chad have been able to take power by winning an outright military victory. Other countries - including Angola, Central African Republic, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, and Sudan - have experienced dramatic conflict that has resulted in mass destruction. Each unhappy African country mired in conflict is different. At a basic level, however, Africa’s wars reflect the difficulty of creating recognised national authorities that actually have physical control over their territories. Much needs to be done in Africa to end conflict: the Africans must take greater ownership, the international community must be pro-active in attempting to avert conflict, and more has to be done to promote development and limit the supply of weapons. All of these causes have been recognised by Africa and the international community and have been subject to considerable study. Individual African states, the African Union and the international community all have roles to play. However, there has been less focus on making Africa’s security agencies work so that conflicts can be prevented or ended. Indeed, it is ironic that just as Africa and the world at large have paid more attention to the problem of conflict across the continent, the language of war, especially the notion of victory and defeat, have been lost. The Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone, and many other rebel/bandit movements in Africa simply need to be defeated. Yet, the countless NGOs and mediators in these conflicts do not want to advocate victory, only that the law of war be followed in the pursuit of victory. While there is clearly not a military solution to every problem, it is also not possible to believe that there is a diplomatic solution to all conflicts. Indeed, the current optimism in Angola springs from the ruling MPLA’s military defeat of the UNITA rebel movement and its seeming resolve to take sensible political steps now that this victory has been achieved. The international community will have to recognise that an actual victory by one side is an important option in some conflicts and work to aid the national authorities in winning, instead of just hoping that they fight well. Thus, there is a role for military victory in Africa and an even more important role for viable security agencies - especially police but also military - that can keep conflict from developing in the first place. The fact that countries with large territories face particularly grave problems of national integration is a clear signal that more has to be done to encourage the everyday provision of security in Africa. Aiding police agencies, in particular, so that they can fight crime, deter criminals, and be viable “first responders” to those who might eventually threaten war is absolutely critical. Yet, the international community is only now taking the first steps toward helping police agencies in Africa. It will have to get beyond the allergy to working with police that developed in the 1960s and 1970s after well-publicised scandals (especially in Latin America) and recognise that focussing on development while simply assuming that security will take care of itself is a careless - and fruitless - strategy. Post-Cold War external intervention in African conflicts has, in the past, been largely guided by a reactive philosophy, with a focus on peacekeeping, for example, rather than preventive diplomacy. This is changing. Peace building along with conflict resolution has become fashionable, though this raises questions too about the lessons from past negotiation experience and the conditions necessary for sustained peace, stability and prosperity. The role of the British government in Sierra Leone in instituting governance structures and standards once they had fought off and pacified the Revolutionary United Front is one example of what can be done in apparently desperate situations. Order has been restored from anarchy in a country once considered beyond salvage. The lessons of the British intervention can be distilled down to the need to assess the utility of traditional UN posture of peacekeeping neutrality as the situation demands, and to build and maintain relationships between civilian and military groups and local and international forces to support the operation. Well-led and resourceful, the UK troops soon gained local support as their methods proved effective. As the situation stabilised in mid-2000, one 19 year-old Sierra Leonean observed, “We love the British soldiers - they are our salvation…. They are well-equipped. They are not as fearful as the UN soldiers. They do not steal from us. We want them to stay.”10 This operation may be a guide to the way future emergencies should be managed, in Liberia and Cote d’Ivoire and elsewhere, though ultimately success can only be measured in terms of Sierra Leone’s ability to remain stable after the British have departed. Conclusion It is now generally thought that the international community did not do enough during the crises of the 1990s, but there is little consensus as to what “doing more” would have entailed. When there is no clear enemy, principles of intervention are indistinct and decisions much more complicated. This is all the more true in geographical areas where there is no direct national interest at stake, and where the threats to peace come not from easily identifiable states but rather non-state or sub-state actors and units. This may point to the need to live with conflict and not interfere in some circumstances, and where involvement is imperative - such as in the case of genocide - to intervene in a manner which is decisive. In all cases, an essential point in addressing Africa’s conflicts is to find methods that give space for local actors to find their own solutions to problems. This article partly draws on the Adelphi Paper,‘The Future of Africa: New Order in Sight?’ by Jeffrey Herbst and Greg Mills, published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies and Oxford University Press (December 2003). Thanks to Brooks Spector for helpful comments on the text. 1.

At click

here.

|

||||||

This site © Crimes of War Project 1999-2004 |

|

By Tom Porteous |

| |

|

By Thierry Cruvellier |

| |

By Paul Collier |

| |

By Greg Mills |

| |

| |

By Pascal Kambale & Anna Rotman |

| |

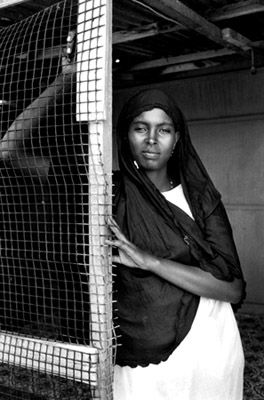

A Photo Essay By Stephen Alvarez |

| |