| October 2004 Resolving

African Conflicts |

||||||||

|

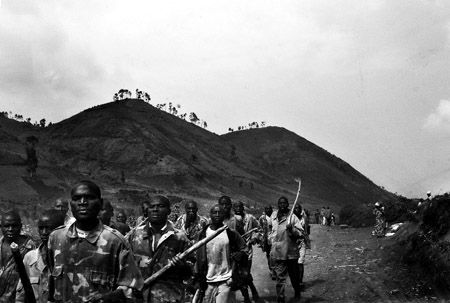

If a storm can be described as perfect, then the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) in the second half of the 1990s was the “perfect war”. Precipitated by the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and the fall of the West’s client kleptocrat, President Mobutu, and his rotten state, the war in DR Congo was dubbed Africa’s First World War. It directly involved the armed forces of six neighbouring states. It drew in factions and rebel groups from other African wars, the remnant armies of defunct neighbouring regimes, and the usual crowd of international profiteers, would-be peacemakers and humanitarians. It was closely connected with armed conflicts in several neighbouring countries, including those in Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Central African Republic, Congo Brazzaville, and Angola. According to one estimate published in 2003 the war may directly and indirectly have caused the deaths of over 4 million people in DR Congo since 1996. As has become increasingly common in Africa the victims were almost all civilians.

The war in DR Congo was but one demonstration of the emptiness of the promises of a post Cold War political and economic renaissance for Africa. There was, it is true, the remarkable transition from apartheid to majority rule in South Africa in 1994. There were also instances of handover to multiparty civilian rule in former one-party or military-ruled states like Ghana, Tanzania, Senegal, Mali, Zambia, Malawi, and even Nigeria. But by the end of the 1990s, any political and economic progress since the end of the Cold War had been overshadowed by a series of old and new wars that now engulfed many parts of the continent and were tipping whole regions further into instability and poverty. In West Africa another regional complex of conflicts, also driven by greed and political disintegration, was in full swing. The late 1990s saw the culmination of the diamond and corruption fuelled rebellion in Sierra Leone that had been going on for a decade. At the start of 2000 a recently signed peace agreement in Sierra Leone was on the brink of failure. Guinea was in danger of being dragged into the conflict. Liberia, nominally at peace after its own war in the first half of the decade but little more than a façade of a state benefiting no one but its gangster-like regime, was still fomenting conflict in all of its neighbours (Sierra Leone, Guinea and Côte D’Ivoire) and was itself edging towards a renewed civil war. Côte D’Ivoire too, once a beacon of prosperity and stability, was increasingly beset by its own internal political troubles that were to develop into armed conflict in 2002. Nigeria, the regional hegemon, was ruled for most of the 1990s by a repressive and corrupt military regime which thrived in part on fomenting ethnic and religious tensions. In the Horn of Africa, Somalia was still without a central government almost a decade after the fall of the last one (the Siad Barre regime which had been backed and armed alternately by both sides in the Cold War). The vacuum of state authority in Somalia left the country in a state of low level conflict and chronic economic weakness, on the one hand vulnerable to external interference and on the other a source of regional instability. To the north of Somalia, border skirmishes between Ethiopia and Eritrea developed into full scale war in 1999. Meanwhile in Sudan, the second phase of the post independence rebellion was well into its second decade and there were no signs of resolution. One peace initiative after another had failed. At the other end of the continent, in Angola, another war that had in an earlier phase been fomented by Cold War rivalry was still raging. Now deprived of their superpower sponsorship, but aided by international businesses which continued to buy the Angolans’ oil and diamonds and sell them weapons, the leaders of both sides (MPLA government and UNITA rebels) were plundering the country to support their war efforts and to fill their foreign bank accounts. In a country fabulously rich in natural resources, including agriculture, the majority of the peasant population were living in desperate poverty, many of them living on food handouts from the international humanitarian relief system. Africa’s wars in the 1990s were all very different in their specifics. But they shared a number of important characteristics. First, one of the main underlying causes of these wars was the weakness, the corruption, the high level of militarization, and in some cases the complete collapse, of the states involved. Secondly, they all involved multiple belligerents fighting for a multiplicity of often shifting economic and political motivations. Thirdly, they all had serious regional dimensions and regional implications. And fourthly they were all remarkable for the brutality of the tactics (ranging from mass murder and ethnic cleansing, to amputation, starvation, forced labour, rape and cannibalism) used by belligerents to secure their strategic objectives.

The Failure to Respond At the United Nations at the end of the Cold War neither the Secretariat nor the Security Council were able or willing to resolve these burgeoning conflicts in Africa. The one UN success in Africa in the post cold war period, the peace operation in Mozambique, was overshadowed by the UN’s failure in Angola in 1992. Then the dramatic US/UN failure in Somalia in 1993-5 rendered the international system helpless in the face of the emerging crisis in central Africa. The permanent members of the UN Security Council stood by and watched, with a negligence verging on complicity as the Hutu nationalist government went about the systematic slaughter of hundreds of thousands of minority Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994 and then launched a belated international humanitarian intervention in eastern Zaire that assisted the genocidaires and helped to spark the war in Zaire. As one neighbouring state after another (many of them recipients of large amounts of Western development aid not to mention “defence” exports) piled into Zaire/Congo in pursuit of its own political, economic and security interests, the UN Security Council failed to respond with any significant political action. In West Africa, peacekeeping and peacemaking for most of the 1990s was left to regional players, notably Nigeria (then ruled by a military dictatorship) which intervened first in Liberia, then in Sierra Leone and Guinea Bissau, under the banner of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). But like the UN in Somalia, ECOWAS became as much part of the problem in those conflicts as the solution. When an elected civilian government came to power in Nigeria in 1999, following the alleged assassination of the billionaire military ruler Sani Abacha, the ECOWAS operation was withdrawn from Sierra Leone and replaced by the UN. After the UN’s dismal record in Africa in the preceding years, Sierra Leone was a do or die test for the UN’s credibility as a force for peace on the continent. Within months the operation was in crisis. In May 2000 the Sierra Leonean rebels, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), tore up the peace deal they had signed with the government and kidnapped over 200 UN peacekeepers. A Watershed In retrospect, the British intervention to rescue the beleaguered UN mission in Sierra Leone is now seen as something as a watershed in the recent evolution of conflicts in Africa. Prime Minister Tony Blair’s decision was taken at short notice in response to a sudden and unexpected crisis. But it had far reaching consequences not just for Sierra Leone but for West Africa, and perhaps for the continent as a whole1. First it reversed the common understanding that had emerged from Somalia and Rwanda that Western military powers were not willing to take military and political risks in Africa unless their vital national interests were at stake. Secondly, it demonstrated that a professional Western military force could bring conflicts in Africa under control at relatively little cost (the UK deployed a few hundred soldiers and lost only one man in combat operations). Thirdly, the British salvaged the UN’s reputation in Africa, not only by saving it from a humiliating failure, but also by subsequently insisting that the UN Security Council strengthen the operation in Sierra Leone so that it should be able to start fulfilling the mandate of bringing permanent peace to Sierra Leone. Fourthly, in Sierra Leone the British and the UN provided a rough template for tackling African wars that went beyond limited humanitarian goals and tried (so far with only limited success) to get to grips with some of the more fundamental political, humanitarian, economic and regional dimensions of a conflict. In West Africa the British intervention in Sierra Leone had a direct impact. Realising that their efforts in Sierra Leone would be brought to nothing unless Charles Taylor, Liberia’s warlord turned President, was contained, the UK browbeat the UN Security Council into imposing economic sanctions on Taylor, a policy which coupled with the growing internal pressure on the Liberian regime led eventually in 2003 to Taylor’s removal from office, a peace agreement between the government and the two rebel factions, and the deployment of a UN peace mission in Liberia. When the political crisis in neighbouring Côte D’Ivoire developed into a civil war in 2002, the example of the British intervention in Sierra Leone encouraged France to intervene with a military force to stabilise the situation in its former colony, to fund a West African peace keeping force (with contributions from the US and Britain), and to play the role of diplomatic midwife in the Ivorian peace process. There is a real possibility that without such a response Côte D’Ivoire would by now have gone the way Liberia and Sierra Leone went in the early 1990s.

Towards Conflict Resolution Elsewhere in Africa there have been other encouraging developments in the past four years. In the Horn, Algeria led a successful US backed peace mission under the banner of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) to mediate an end to the border war between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Once a deal was signed in 2000, the UN deployed a peacekeeping mission along the front line to monitor the ceasefire. In Sudan the situation is more complicated. Although a provisional peace agreement has been signed between the government and the southern rebels, perhaps marking an end to the war that has continued since 1983, a new conflict has broken out in the western province of Darfur. This war has been accompanied by repeated attacks against non-Arab civilians by Arab tribal militias known as Janjaweed, who have been supported by the Khartoum government and its armed forces. Outside states that have been influential in promoting the North-South peace process now face the risk that the progress they have achieved will unravel if they punish the Sudanese government for its apparent support of ethnic cleansing in Darfur. In the Horn’s most troubled and “failed” state, Somalia, there has been little progress. The country remains without a central government and current peace negotiations are unlikely to go anywhere. However in the breakaway and largely peaceful north western “statelet” of Somaliland there has been remarkable progress towards peace and political stabilisation leading to was a smooth and democratic transition of power following the death of President Mohammad Ibrahim Egal in 2002. In southern Africa, Angola’s war is over. In 2002 the UNITA (National Union for Total Independence of Angola) rebels were defeated, their leader Jonas Savimbi was killed, and the rebel leadership accepted a peace agreement more or less on the government’s terms. This has been achieved with little or no formal external involvement (though foreign military advisers helped the government deliver the military coup de grace to UNITA). Elsewhere in the region in 2002 an incipient conflict in Madagascar after a stolen election was nipped in the bud thanks to some intense international diplomacy involving African and non African governments. There has been and continues to be a serious political deterioration in Zimbabwe. But in spite of dire warnings of civil war and an undercurrent of political violence and assassinations this crisis has so far not developed into a full blown armed conflict nor is it easy to see how it could in the near future. In central Africa one hesitates to speak of an improvement. Certainly in Burundi, in Eastern DR Congo, in the Central African Republic and in northern Uganda there has been much killing (mostly of civilians) in the past couple of years. And yet thanks to a coalition of efforts by the UN, South Africa, the African Union, Tanzania, Botswana, the EU, the US and others, there has been some progress in moving forward peace processes in the main conflicts of the region, namely in Burundi and in the DR Congo. Most of the foreign troops formally withdrew from DR Congo according to the terms of a peace agreement in 2002. After painstaking negotiations a transitional national government comprising the main political groups was formed in 2003. The role of the UN (which deployed a peacekeeping force, MONUC, in 2000) has gradually been strengthened. When UN peacekeepers found they were unable to deal with an escalation of violence and ethnic massacres by rival tribal militias in Ituri (Eastern DR Congo) in 2003, the French dispatched a rapid reaction force under the banner of the EU, with a contribution from the UK, Belgium and others (an unprecedented arrangement that would have been unthinkable just a couple of years ago). This force was able to secure the main town in Ituri and parts of the surrounding region until the UN could be given the means (mandate and troops) to do the job itself. Elsewhere in Central Africa, Africans themselves have sought to impose military solutions with mixed results: in Congo Brazzaville the Angolan army intervened successfully to end a civil war by ousting an elected government and installing their own ally; in northern Uganda the government’s eighteen month old military campaign to suppress the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army, has not yet succeeded and indeed the situation there is again a cause for real concern. Explanations for Success It would be futile to search for a single explanation for what appears for now to be a trend towards the resolution of African conflicts. Africa’s wars are as heterogeneous as its many nations and communities. The reasons why Angola’s conflict came to end are quite different from the reasons why the belligerents in Sudan’s civil war have been willing to engage seriously in peace talks. However some of the successes of the past three years can be attributed in part to a mixture of fatigue on the part of those fighting African wars and to the fact that both Africans and non-Africans are learning lessons from the many failures of the past fifteen years, are coming up with more creative proposals and solutions to tackle the problem of conflict, and are readier to take risks in implementing them. Although the details vary widely from conflict to conflict, the basic ingredients of resolution remain the same - a combination of military, diplomatic, humanitarian, and economic action delivered by a more or less complex coalition of local, regional and international actors.

At the UN, following the publication of a hard hitting report2 in 2000 on UN peacekeeping operations, there has been significant improvement in planning and capacity at the Department for Peacekeeping Operations. There also appears to be a new readiness on the part of the Security Council (which prior to the Iraq crisis devoted a majority of its time to deliberating about conflicts in Africa) to equip UN missions in Africa and elsewhere with the mandate and capacity to do their job (once the UN operation in Liberia is fully deployed, the three largest UN peacekeeping operations in the world will all be in Africa). Crucially there is also now a UN Security Council acknowledgement of the imperative to incorporate the protection of civilians into the mandates of UN and other peace support operations. Other UN mechanisms have also been deployed to help nudge African conflicts towards resolution including special panels to monitor sanctions in Angola, Liberia and Somalia, a special panel monitoring the links between conflict and the exploitation of resources in DR Congo, international war crimes tribunals for Rwanda and Sierra Leone and the establishment of a special UN office headed by a senior official to examine the many regional dimensions of conflict in West Africa. In Africa itself, there is a new recognition among leaders like South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki, Senegal’s Abdoulaye Wade, Ghana’s John Kuffuor, Nigeria’s Olusegun Obasanjo, and the new Chairman of the African Union (AU), Alpha Omar Konare, of the negative impact of Africa’s wars on the prospects for the whole continent and a determination that Africans themselves should play a more active and creative role in ending wars. As usual there is a lot of rhetoric. But there is some substance too. The new mood (symbolised by Mbeki’s ambitious blueprint for an African renaissance, the New Partnership for African Development3) has been translated into some successful African peace initiatives on the ground (e.g. in Burundi and DR Congo) and into a programme to reform Africa’s own regional security communities4 and to increase Africa’s own peacekeeping capacity. Among the big Western powers, particularly the US, the French and the UK, there has been a greater engagement on Africa at a higher political level and a greater willingness to bury past differences on Africa and co-operate. This has been in part because of a real sense of guilt at the failure of the West to prevent or halt the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. But it is also because of a new post 9/11 consensus in the West that, quite apart from humanitarian concerns, there are compelling strategic reasons (oil, Islam and terrorism) for preventing Africa from slipping further into poverty and conflict. In policy terms these factors have led to greater support for Africa’s own efforts to deal with conflict, support for beefed up UN operations and, when all else fails, a greater preparedness to commit Western troops in response to African crises. The Remaining Challenges But, in spite of these developments, one can hardly say with great conviction that the tide of conflict in Africa that gathered during the Cold War and engulfed the continent in the 1990s has finally turned. The UN and others may now be implementing passably effective crisis response and conflict resolution strategies, but they are still struggling to develop effective models for conflict prevention and for post conflict economic and political transition that can deliver sustainable peace. Even in Sierra Leone, a relatively small country where the British government and others have invested millions of dollars in a large, multi-sectoral peace building effort, the situation remains precarious and, without long term international commitment, unsustainable. Ending hostilities and stabilisation have proved to be the easiest tasks. Much more difficult, time consuming and expensive is the job of rebuilding a state which has almost completely disintegrated and creating a political, economic, judicial and social environment in which the risk of a return to conflict is eliminated, or at least minimised. If this is hard in tiny Sierra Leone then it is going to be a many times more so in a DR Congo or a Sudan. Now that so many conflicts in Africa are moving towards some sort of resolution, there is a real opportunity for action. The urgent task is to regenerate states which have already collapsed into conflict and to strengthen those which are in danger of doing so. The broad outlines of what needs to be done are fairly clear. At a state level the transition can only take place through locally owned processes of consultation that tackle head on such crucial questions as political legitimacy and the quality of citizenship and political participation; transparency, accountability, and the management of economic resources; the reform of the security sector and the demilitarisation of politics; the establishment of the rule of law; and reconciliation and accountability for war crimes. Concurrently, at a regional level more work and resources are required to improve and implement the current programme to reform and expand Africa’s regional security communities like those envisaged by the AU and ECOWAS. It is only through regional co-operation that states emerging from conflict can address important regional dimensions of conflict like migration, refugees, organised crime and cross border trafficking in illegally exploited resources and arms. More action at every level is also needed to tackle the HIV/AIDS crisis which threatens fatally to undermine state capacity even in stronger African states and accentuate all the political and economic problems associated with weak states and internal conflict. The problem is vast, immediate and highly threatening.

The industrialised rich countries can assist with all these tasks, problems and processes - principally with financial and technical support - but they should be careful to ensure that their political, economic, humanitarian and military interventions, however well intended, do not undermine transitional processes by imposing prescriptive blueprints or by providing support to those forces which stand to benefit from the weakness of the state and from war. They also need to do much more, if they are really serious about ending African conflicts, to deal with those negative aspects of the global economy and global governance that tend to disadvantage Africa, undermine African states, and directly or indirectly fuel African wars. These include: trade barriers in rich countries that block Africa’s access to rich countries’ markets; insufficient conditionality on development aid; Africa’s massive debt burden to rich countries (Africa is still paying more to the industrialised world in debt servicing than it receives in foreign aid); the unchecked flows of arms which continue to pour into Africa from manufacturers and dealers in the West; and the gaping legislative loopholes which continue to allow multinational companies and banks to benefit from the abusive, sometimes criminal, exploitation of resources and from high level corruption in conflict prone countries in Africa. At least some of these key issues are now being debated in international policy circles thanks in part to sustained lobbying by some NGOs and a few voices in the media. There was even a vague promise to address some of these problems in the 2002 G8 Africa Action Plan (though the plan is carefully drafted to avoid concrete commitments on the most sensitive issues). Modest progress has been made in some specific areas: for example the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme5 to control the trade in “conflict diamonds”. But there has been nothing significant on trade, nothing on arms and little on controlling corporate behaviour. Much more work is required to reconcile the stated commitment of the leaders of the industrialised world to work to end conflict in Africa with the political and economic interests that apparently make it so difficult for them to end agricultural subsidies for their farmers, to stop propping up corrupt or repressive governments with economic and military assistance, and to rein in the arms dealers, corporations and banks which continue to make vast profits from political instability in Africa. Finally, there is now a formidable new challenge: not to let the so-called “global war on terror”, undermine the progress that Africa has made in the past few years towards resolving conflicts. The huge cost of the war in Iraq and its aftermath should not be allowed to divert attention, money and expertise away from the job of post conflict reconstruction in Africa. Nor should the US, EU and UK’s post 9/11 concerns about security and “failed states” be allowed to skew Western agendas in Africa in favour of counter-terrorism, military control and oil security, and away from human rights, social justice, political participation, and corporate responsibility. Only by promoting the latter can real peace and security, both for Africa and for the West, be achieved. 1. It can be argued that the consequences went even further than Africa. It is possible that the success of the UK military operation in Sierra Leone strengthened Mr. Blair’s belief in the viability of military solutions and thus encouraged him to embrace the idea that military “humanitarian” intervention in Iraq was both morally necessary and likely to succeed. 2. http://www.un.org/peace/reports/peace_operations/report.htm 4. The African Union (AU) - which succeeded the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 2000 and is soon to establish its own a Peace and Security Council - the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Conference on Security, Stability, Development and Cooperation in Africa (CSSDCA), among others. 5. http://www.kimberleyprocess.com/

|

||||||||

This site © Crimes of War Project 1999-2004 |

By Tom Porteous |

| |

By Thierry Cruvellier |

| |

By Paul Collier |

| |

By Greg Mills |

| |

| |

By Pascal Kambale & Anna Rotman |

| |

A Photo Essay By Stephen Alvarez |

| |